A Brief History of Scaling LinkedIn

I wrote this post originally as an article published on the LinkedIn engineering blog.

LinkedIn started in 2003 with the goal of connecting to your network for better job opportunities. It had only 2,700 members the first week. Fast forward many years, and LinkedIn’s product portfolio, member base, and server load has grown tremendously.

Today, LinkedIn operates globally with more than 350 million members. We serve tens of thousands of web pages every second of every day. We've hit our mobile moment where mobile accounts for more than 50 percent of all global traffic. All those requests are fetching data from our backend systems, which in turn handle millions of queries per second.

So, how did we get there?

The early years

Leo

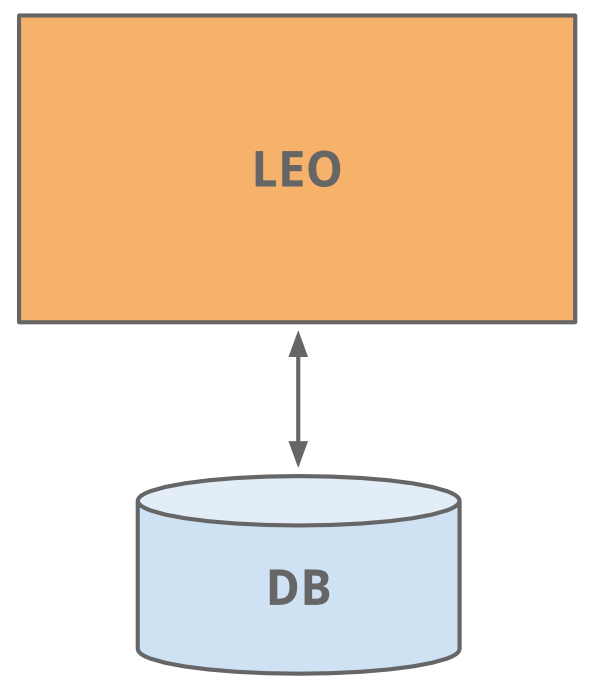

LinkedIn started as many sites start today, as a single monolithic application doing it all. That single app was called Leo. It hosted web servlets for all the various pages, handled business logic, and connected to a handful of LinkedIn databases.

Ah, the good old days of website development - nice and simple

Member Graph

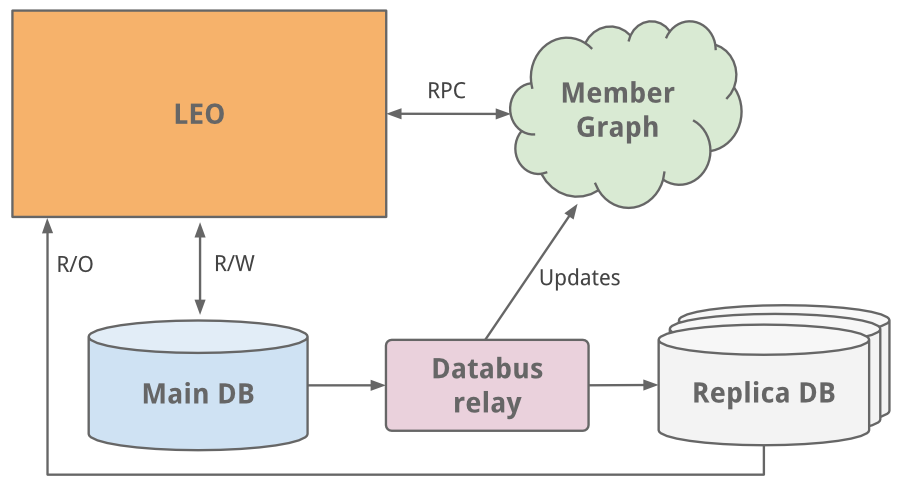

One of the first things to do as a social network is to manage member to member connections. We needed a system that queried connection data using graph traversals and lived in-memory for top efficiency and performance. With this different usage profile, it was clear it needed to scale independently of Leo, so a separate system for our member graph called Cloud was born - LinkedIn’s first service. To keep this graph service separate from Leo, we used Java RPC for communication.

It was around this time we needed search capabilities. Our member graph service started feeding data into a new search service running Lucene.

Replica read DBs

As the site grew, so did Leo, increasing its role and responsibility, and naturally increasing its complexity. Load balancing helped as multiple instances of Leo were spun up. But the added load was taxing LinkedIn’s most critical system - its member profile database.

An easy fix we did was classic vertical scaling - throw more CPUs and memory at it! While that bought some time, we needed to scale further. The profile database handled both read and write traffic, and so in order to scale, replica secondary DBs were introduced. The replica DBs were a copy of the member database, staying in sync using the earliest version of databus (now open-sourced). They were set up to handle all read traffic and logic was built to know when it was safe (consistent) to read from a replica versus the main DB.

While the main-replica model worked as a medium-term solution, we’ve since moved to partitioned DBs

As the site began to see more and more traffic, our single monolithic app Leo was often going down in production, it was difficult to troubleshoot and recover, and difficult to release new code. High availability is critical to LinkedIn. It was clear we needed to “Kill Leo” and break it up into many small functional and stateless services.

"Kill Leo" was the mantra internally for many years...

Service Oriented Architecture

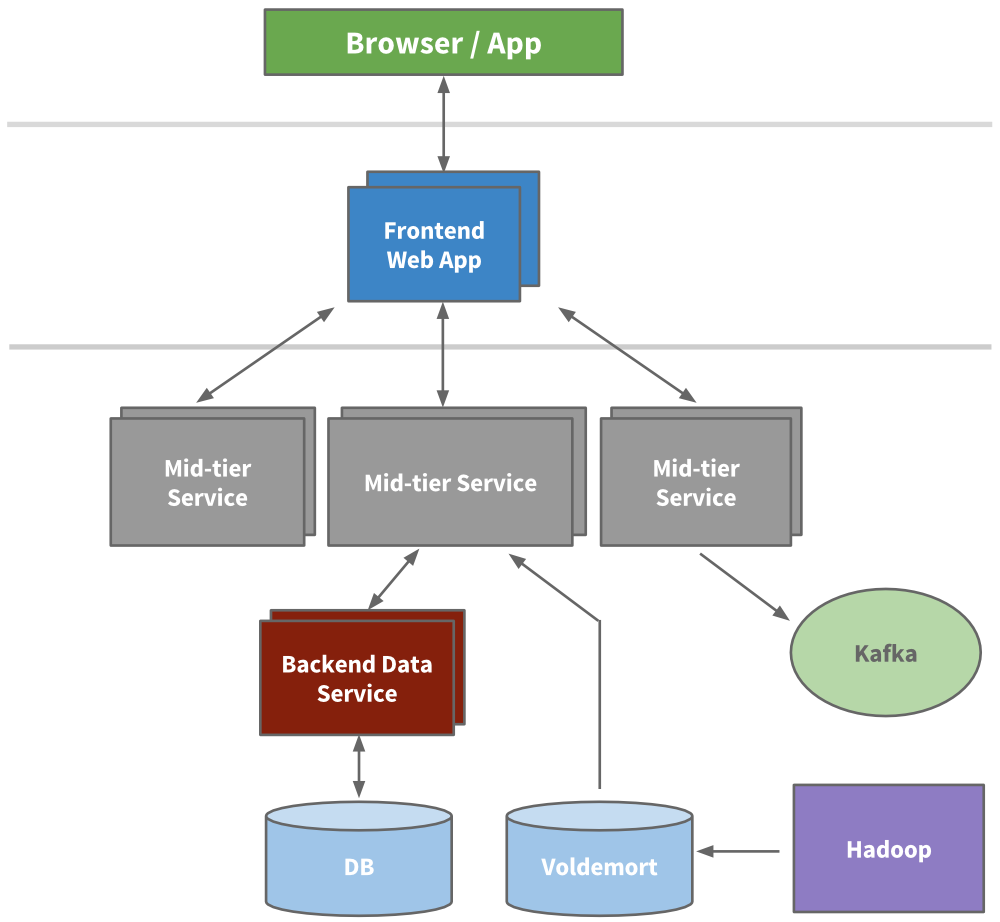

Engineering started to extract micro services to hold APIs and business logic like our search, profile, communications, and groups platforms. Later, our presentation layers were extracted for areas like our recruiter product or public profile. For new products, brand new services were created outside of Leo. Over time, vertical stacks emerged for each functional area.

We built frontend servers to fetch data models from different domains, handle presentation logic, and build the HTML (via JSPs). We built mid-tier services to provide API access to data models and backend data services to provide consistent access to its database(s). By 2010, we already had over 150 separate services. Today, we have over 750 services.

An example multi-tier service oriented architecture within LinkedIn

Being stateless, scaling could be achieved by spinning up new instances of any of the services and using hardware load balancers between them. We actively started to redline each service to know how much load it could take, and built out early provisioning and performance monitoring capabilities.

Caching

LinkedIn was seeing hypergrowth and needed to scale further. We knew we could reduce the load altogether by adding more layers of cache. Many applications started to introduce mid-tier caching layers like memcache or couchbase. We also added caches to our data layers and started to use Voldemort with precomputed results when appropriate.

Over time, we actually removed many mid-tier caches. Mid-tier caches were storing derived data from multiple domains. While caches appear to be a simple way to reduce load at first, the complexity around invalidation and the call graph was getting out of hand. Keeping the cache closest to the data store as possible keeps latencies low, allows us to scale horizontally, and reduces the cognitive load.

Kafka

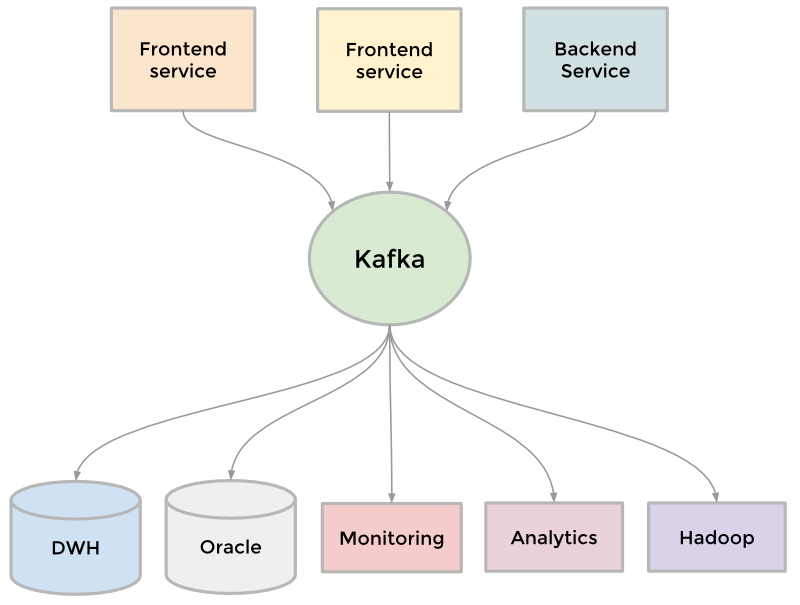

To collect its growing amount of data, LinkedIn developed many custom data pipelines for streaming and queueing data. For example, we needed our data to flow into data warehouse, we needed to send batches of data into our Hadoop workflow for analytics, we collected and aggregated logs from every service, we collected tracking events like pageviews, we needed queueing for our inMail messaging system, and we needed to keep our people search system up to date whenever someone updated their profile.

As the site grew, more of these custom pipelines emerged. As the site needed to scale, each individual pipeline needed to scale. Something had to give. The result was the development of Kafka, our distributed pub-sub messaging platform. Kafka became a universal pipeline, built around the concept of a commit log, and was built with speed and scalability in mind. It enabled near realtime access to any data source, empowered our Hadoop jobs, allowed us to build realtime analytics, vastly improved our site monitoring and alerting capability, and enabled us to visualize and track our call graphs. Today, Kafka handles well over 500 billion events per day.

Kafka as the universal data stream broker

Inversion

Scaling can be measured across many dimensions, including organizational. In late 2011, LinkedIn kicked off an internal initiative called Inversion. This initiative put a pause on feature development and allowed the entire engineering organization to focus on improving tooling and deployment, infrastructure, and developer productivity. It was successful in enabling the engineering agility we need to build the scalable new products we have today.

The modern years

Rest.li

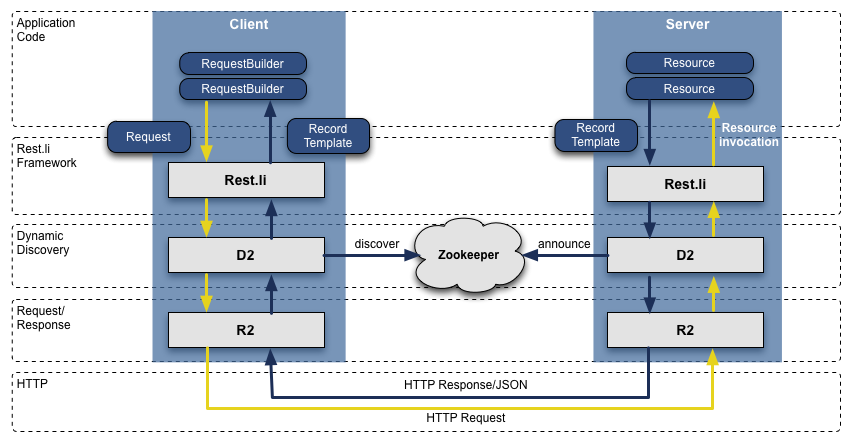

When we transformed from Leo to a service oriented architecture, the APIs we extracted assumed Java-based RPC, were inconsistent across teams, were tightly coupled with the presentation layer, and it was only getting worse. To address this, we built out a new API model called Rest.li. Rest.li was our move towards a data model centric architecture, which ensured a consistent stateless Restful API model across the company.

By using JSON over HTTP, our new APIs finally made it easy to have non-Java-based clients. LinkedIn today is still mainly a Java shop, but also has many clients utilizing Python, Ruby, Node.js, and C++ both developed in house as well as from tech stacks of our acquisitions. Moving away from RPC also freed us from high coupling with presentation tiers and many backwards compatibility problems. Plus, by using Dynamic Discovery (D2) with Rest.li, we got automated client based load balancing, discovery, and scalability of each service API.

Today, LinkedIn has over 975 Rest.li resources and over 100 billion Rest.li calls per day across all our datacenters.

Rest.li R2/D2 tech stack

Super Blocks

Service oriented architectures work well to decouple domains and scale services independently. But there are downsides. Many of our applications fetch many types of different data, in turn making hundreds of downstream calls. This is typically referred to as a “call graph”, or “fanout” when considering all the many downstream calls. For example, any Profile page request fetches much more beyond just profile data including photos, connections, groups, subscription info, following info, long form blog posts, connection degrees from our graph, recommendations, etc. This call graph can be difficult to manage and was only getting more and more unruly.

We introduced the concept of a super block - groupings of backend services with a single access API. This allows us to have a specific team optimize the block, while keeping our call graph in check for each client.

Multi-Data Center

Being a global company with a fast growing member population, we needed to scale beyond serving traffic from one data center. We began an effort years ago to address this, first by serving public profiles out of two data centers (Los Angeles and Chicago). Once proven, we embarked on enhancing all our services to handle data replication, callbacks from different origins, one-way data replication events, and pinning users to a geographically close data center.

Many of our databases run on Espresso (a new in-house multi-tenant datastore). Espresso was built with multi data centers in mind. It provides master / master support and handles much of the difficult replication.

Multiple data centers are incredibly important to maintain “site-up” and high availability. You need to avoid any single point of failure not just for each individual service, but the entire site. Today, LinkedIn runs out of three main data centers, with additional PoPs around the globe.

LinkedIn's operational setup as of 2015 (circles represent data centers, diamonds represent PoPs)

What else have we done?

Of course, our scaling story is never this simple. There’s a countless number of things we’ve done over the years across all engineering and operations teams, including some of these larger initiatives:

Many of our most critical systems have their own rich history and evolution to address scale over the years. This includes our member graph service (our first service outside from Leo), search (our second service), news feed, communications platform, and member profile backend.

We’ve built data infrastructure that enables long term growth. This was first evident with Databus and Kafka, and has continued with Samza for data streams, Espresso and Voldemort for storage solutions, Pinot for our analytics systems, as well as other custom solutions. Plus, our tooling has improved such that developers can provision this infra automatically.

We’ve developed a massive offline workflow using Hadoop and our Voldemort data store to precompute data insights like People You May Know, Similar profiles, Notable Alumni, and profile browse maps.

We’ve rethought our frontend approach, adding client templates into the mix (Profile page, University pages). This enables more interactive applications, requiring our servers to send only JSON or partial JSON. Plus, templates get cached in CDNs and the browser. We also started to use BigPipe and the Play framework, changing our model from a threaded web server to a non-blocking asynchronous one.

Beyond the application code, we’ve introduced multiple tiers of proxies using Apache Traffic Server and HAProxy to handle load balancing, data center pinning, security, intelligent routing, server side rendering, and more.

And finally, we continue to improve the performance of our servers with optimized hardware, advanced memory and system tuning, and utilizing newer Java runtimes.

What’s next

LinkedIn continues to grow quickly and there’s still a ton of work we can do to improve. We’re working on problems that very few ever get to solve - come join us!

Thanks to Steve, Swee, Venkat, Eran, Ram, Brandon, Mammad, and Nick for the help in reviewing.

In addition to this post I wrote on the LinkedIn Engineering Blog, I put together a visual slideshow to accompany this post: